Link

https://awetton.itch.io/shieldbot

Overview

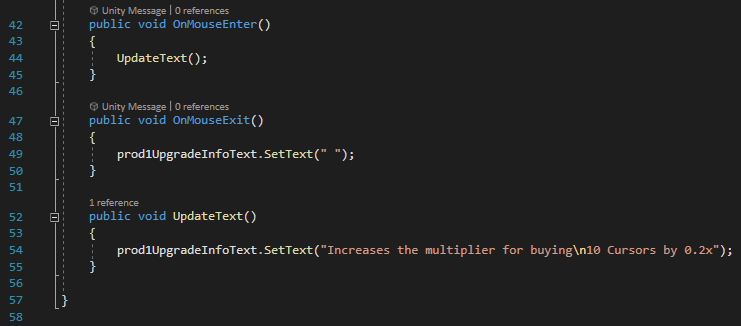

Instead of a regular platformer where the objective is to travel across a stage to reach a specified end goal, I decided to make my platformer game more of an arena survival style game. By rotating a shield around the player character using your mouse cursor, the objective is to survive an endless onslaught of infinitely spawning enemies for as long as possible before you die.

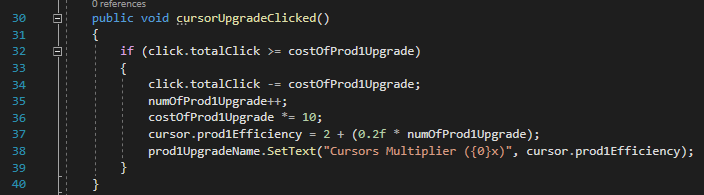

Shield

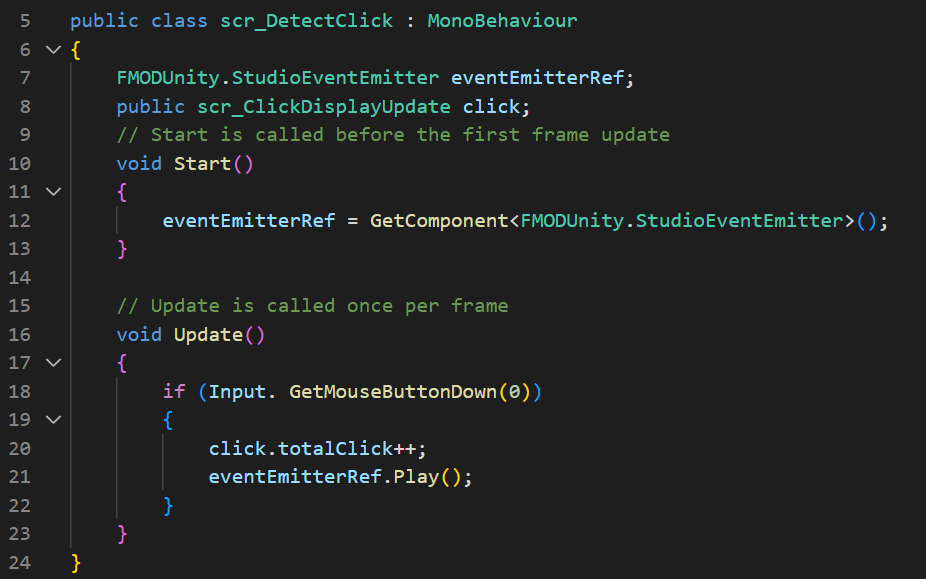

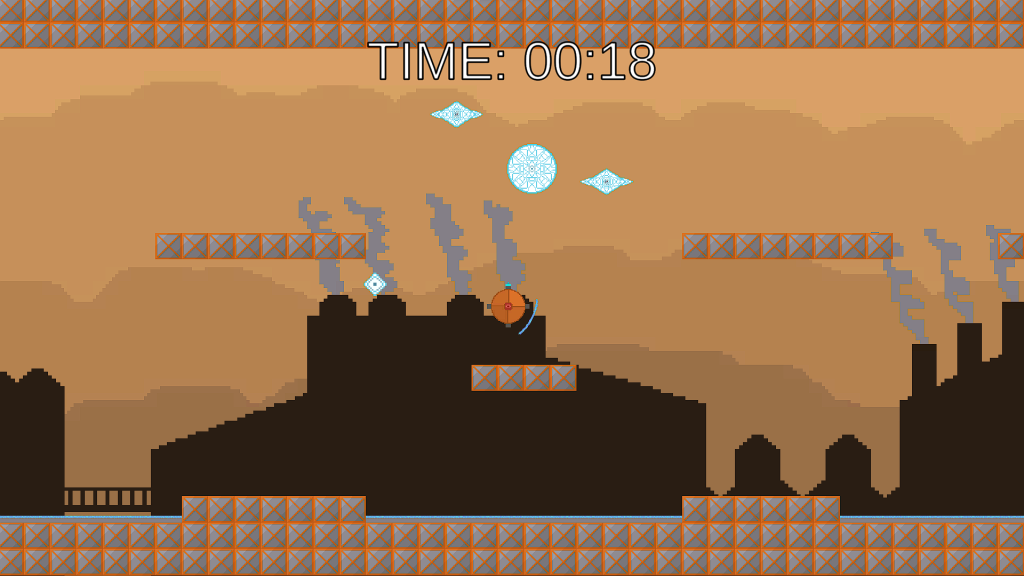

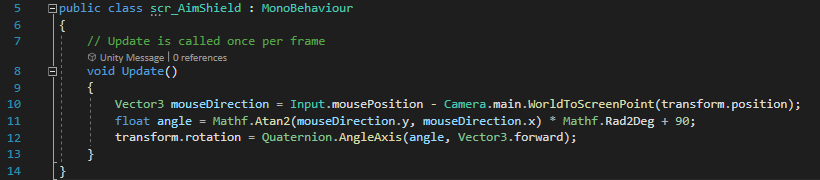

The main feature of this game is the player’s shield. The actual object of the collision checker is actually located at the center of the player’s sprite, but the capsule collider is offset to the outside. This means that by simply rotating the object, the collider will orbit the player without needing to worry about how to change the coordinates to make it move in a circle.

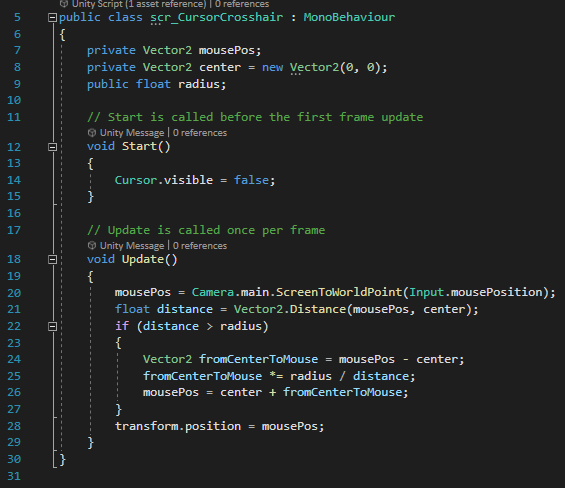

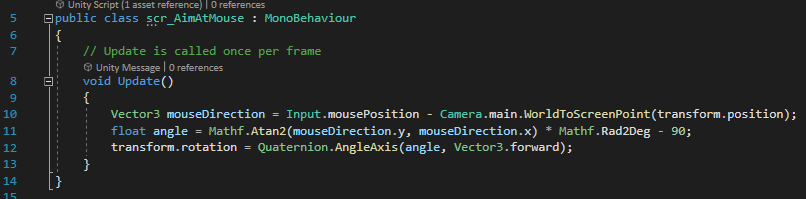

This rotation is controlled by this script, which angles the object in the direction of the cursor. This allows quick and easy control over where the shield is pointing, suiting the fast paced gameplay.

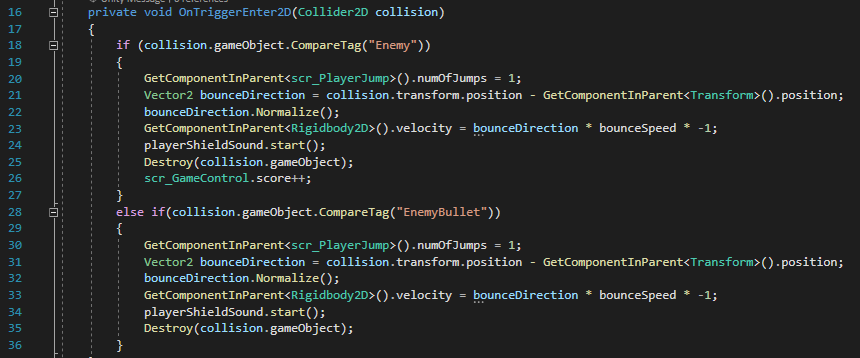

When the player hits an enemy with their shield, it is destroyed, and the player is bounced vertically away from the enemy. This can be helpful if the player is launched upwards, but can also launch the player downwards, potentially into spikes or other enemies. Originally, I wanted to also bounce the player horizontally, but I could not find any way to make it work, as the velocity was instantly reset by any horizontal inputs.

Player Animations

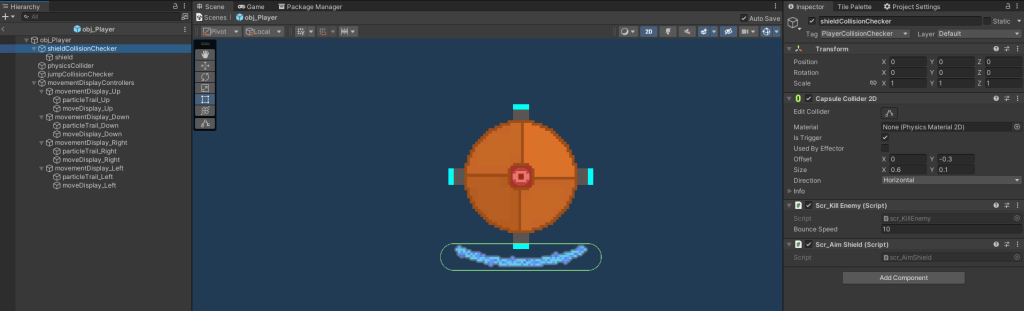

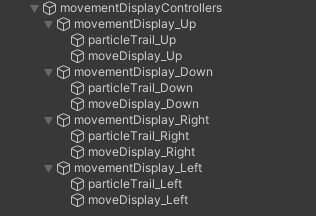

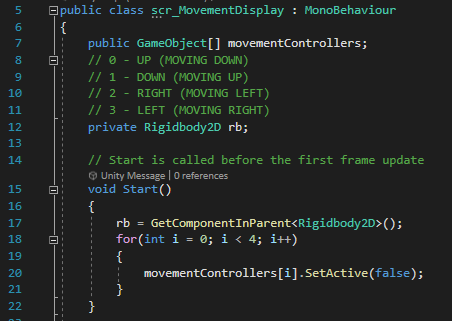

Using a combination of simple rectangle objects and particle trails, I created a simple animation system for the player, where the object and trail are enabled on the side opposite to the movement of the player in order to appear like a thruster is activating.

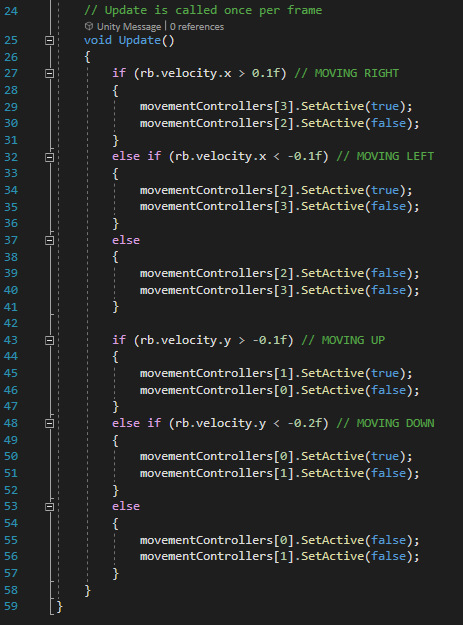

This is done by first assigning each “movementDisplay_[direction]” object into a list of game objects within the script, and setting each one’s “SetActive” value to false. This disables the objects, making them invisible and non-functional.

Then, each frame, the script checks the velocity of the player to see what direction they are moving in, and enables the object on the opposite side to the movement. For example, if the player is moving to the right (making their x velocity a positive number) the script will enable the object and trail on the left of the sprite, appearing as a thruster pushing the player in the direction of their movement. The thruster for moving upwards is set to be active even if the player isn’t moving, to appear to be making the player hover in the air even with no movement.

Camera

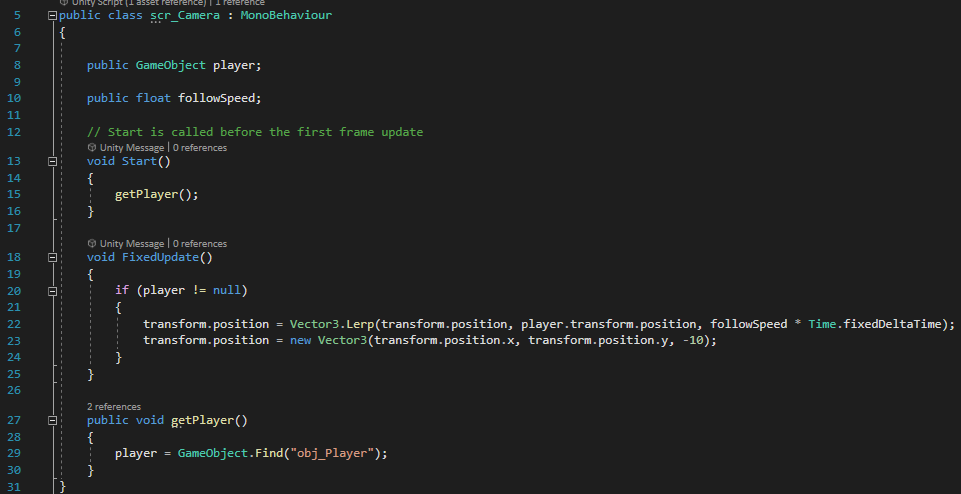

The camera in this game moves with the player, unlike the other prototypes where it stays in one static position. It does not perfectly follow the player, instead following at a slightly slower speed, which shows the player’s movement more clearly and feels more natural for the player.

Parallax Background

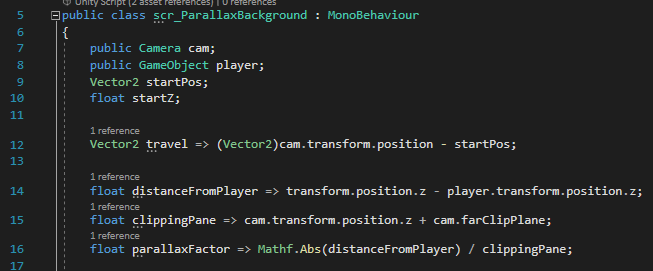

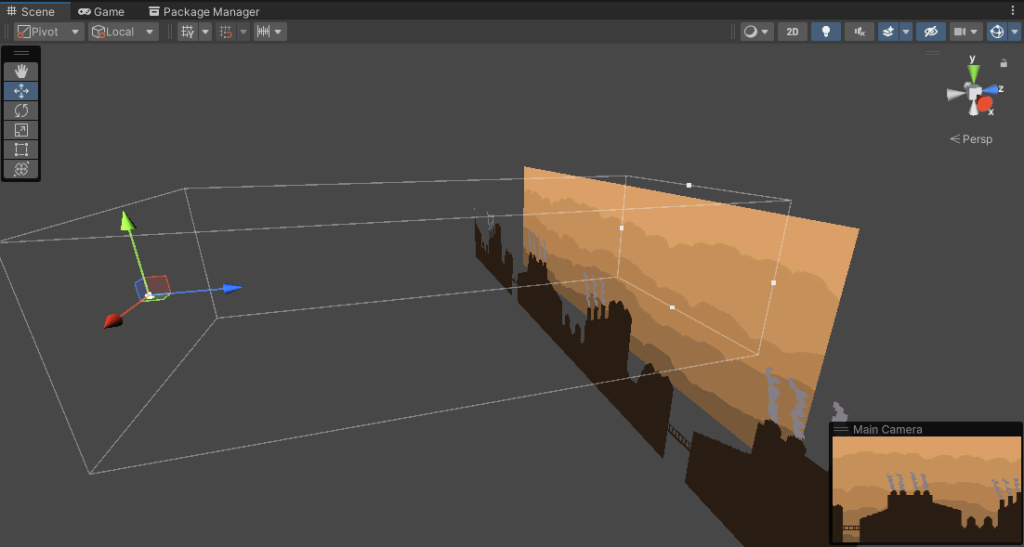

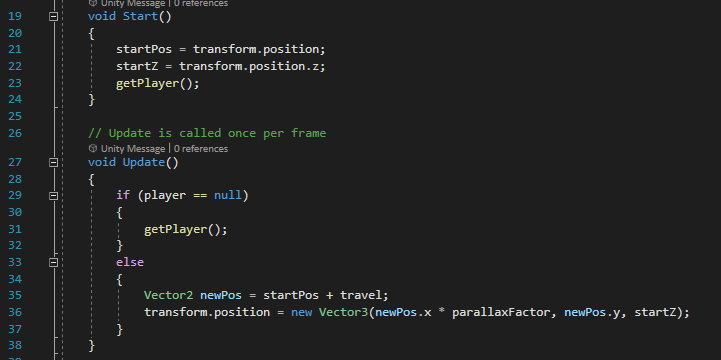

To make the game appear more visually interesting, I created a parallax background, with different layers of the background moving at different speeds with the player to give the appearance of distance between them. I did this by following an online tutorial (AdamCYounis (2021) The Perfect Pixel Art Parallax Tutorial [and Unity script] [Video]. Available online: https://youtu.be/tMXgLBwtsvI), which allowed me to learn how to write the script.

The bottom 3 variables are specially assigned; the => symbol means that every time the variable is called, it will recalculate its value, ensuring it is always accurate. The parallax background works by calculating the distance between the player and the backgrounds, which are positioned further away from the camera in the z-axis. While this isn’t visible from the 2D camera view, the distance can be used to calculate the parallax factor, which is a value that the movement of the background images can be multiplied by to make them move slower than the player. The images are also tiled to ensure that the player does not go past the edges of them.

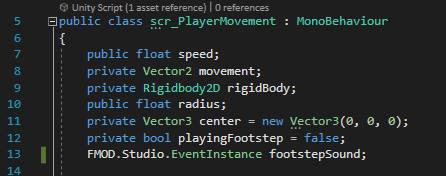

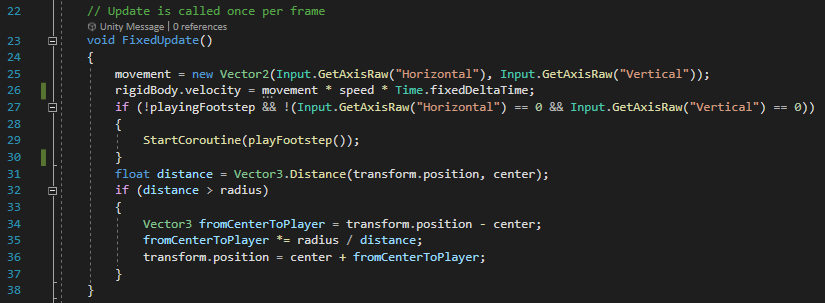

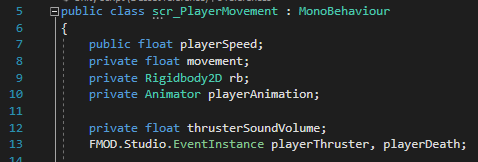

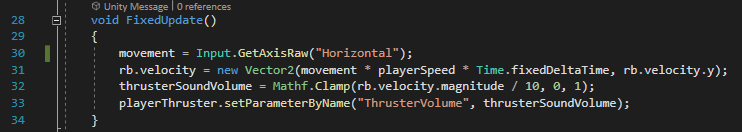

Player Movement

The player’s movement is divided into two scripts – one for the horizontal movement, and a separate script for the jumping.

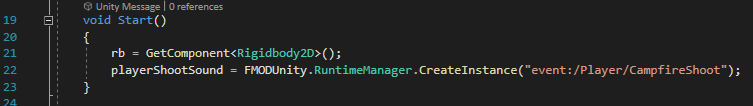

The horizontal movement is once again similar to that used in the Space Invaders and Top Down Shooter games – simply setting the “movement” variable to the horizontal input built in to Unity, and using it to create a vector that is assigned to the Rigidbody2D component’s velocity after being multiplied by the playerSpeed variable and Time.fixedDeltaTime to account for frame rate.

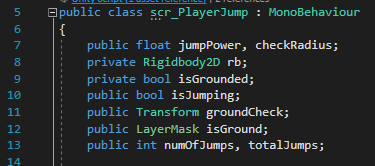

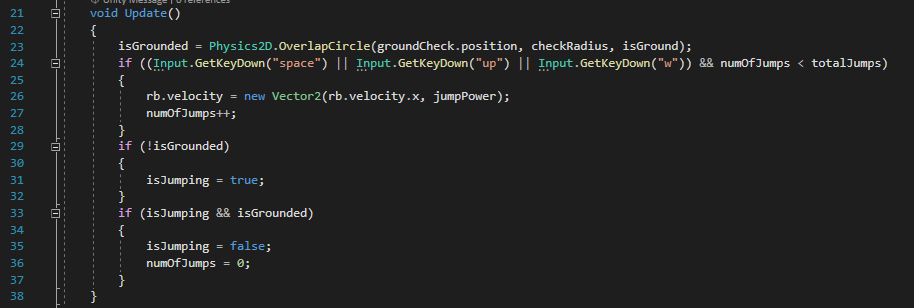

The vertical movement is slightly more complex. In order to let the player double jump, two integer variables – numOfJumps and totalJumps – are required. numOfJumps tracks how many times the player has jumped since touching the ground, and totalJumps represents the maximum number of times the player can jump before needing to touch the ground again to be able to jump any more.

When the player presses the jump key (Spacebar, W, or the Up Arrow), if the numOfJumps integer is lower than the totalJumps integer, their vertical velocity is set to the value of the jumpPower variable, and numOfJumps is increased by one. When the player is touching the ground, which is calculated using a physics circle centered on a game object at the bottom of the character’s sprite, the isGrounded boolean is set to true, and when they aren’t, the isJumping boolean is set to true. If both isJumping and isGrounded are true at the same time, then that means the player has just landed from a jump. isJumping is then set to false, and the numOfJumps is set to 0, allowing the player to double jump again.

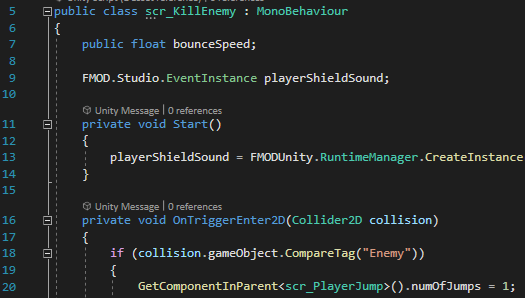

When the player kills an enemy by hitting it with their shield, their numOfJumps is set to 1. This means that if the player double jumps, then kills an enemy, they can jump again in mid air, potentially allowing them to change jumps in combination with the bounce that killing enemies gives.

Maps

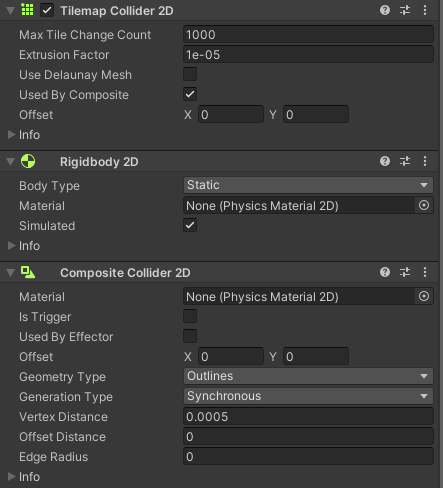

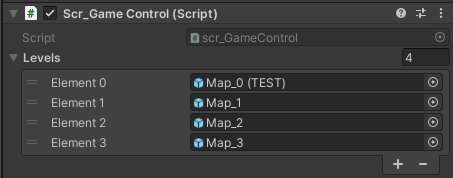

Instead of having just one map that would be repeated, I created 3 separate prefabs of maps, each with their own unique layout. Each was made using the Tile Palette tool, which allowed for quick and easy placement of walls, floors, and platforms, without having to manually create the colliders for each.

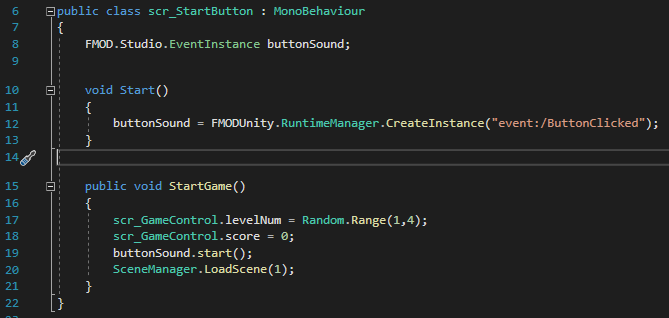

When the game is loaded from the main menu, the “levelNum” variable is assigned to a random value from 1 to 3. This is then used to select which map will be loaded from a list located on the game controller object on the scene of the main game.

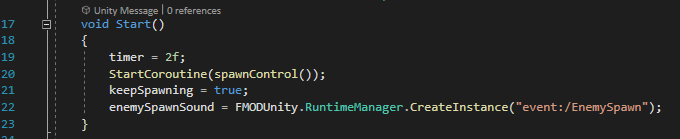

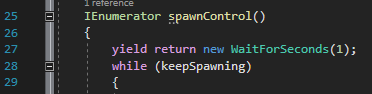

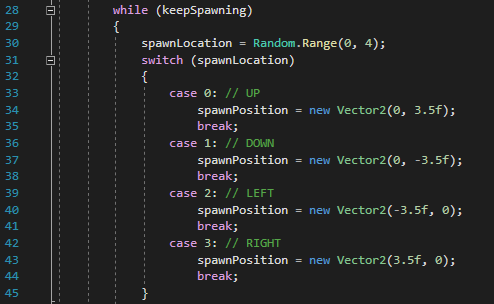

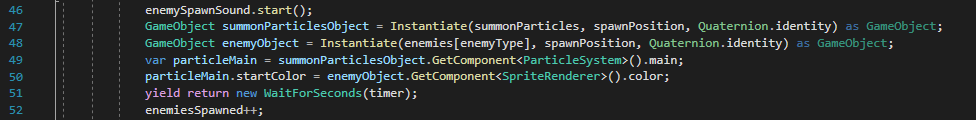

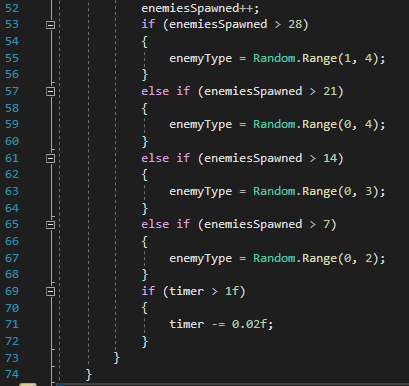

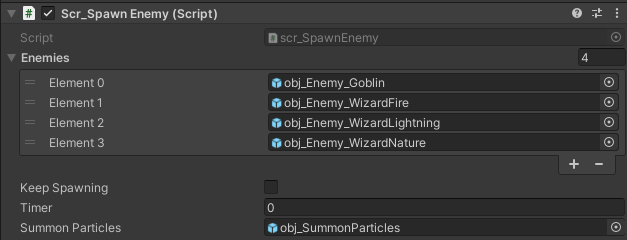

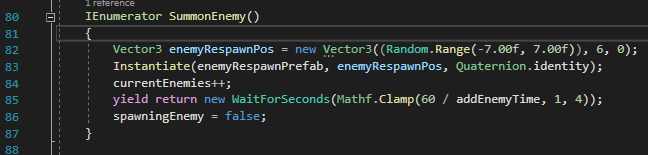

Spawning

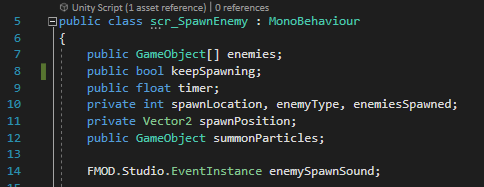

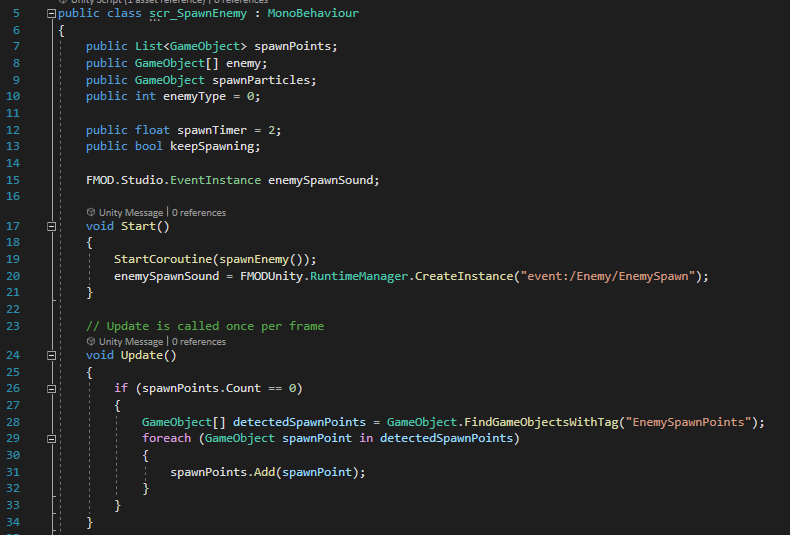

Each of the three map preset has a selection of spawn point objects. These are used to calculate where to spawn enemies.

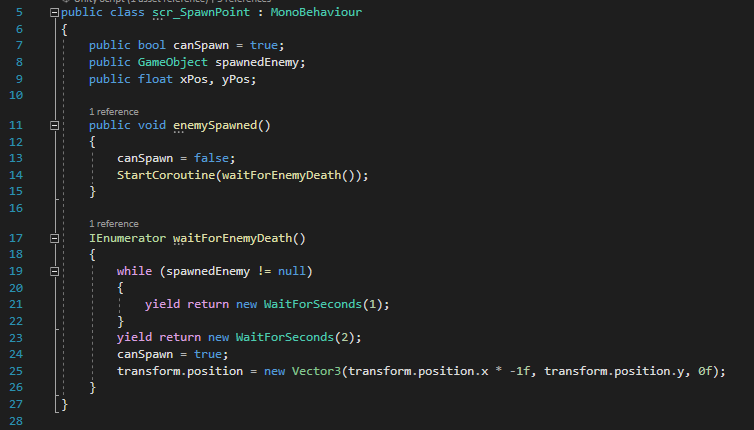

As soon as the map is loaded, the scr_SpawnEnemy script will detect all of the objects with the “EnemySpawnPoints” tag, and add them to a list of all spawn point objects.

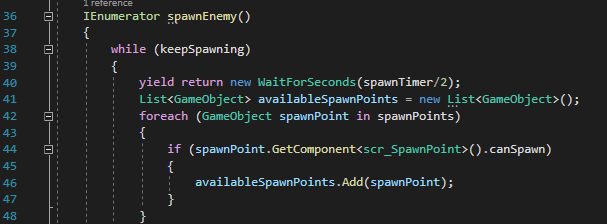

The spawnEnemy coroutine will wait for half of the spawnTimer duration, and then check each spawn point object for their canSpawn boolean. If the boolean is true, it will be added to a list of available spawn points for the next enemy spawn.

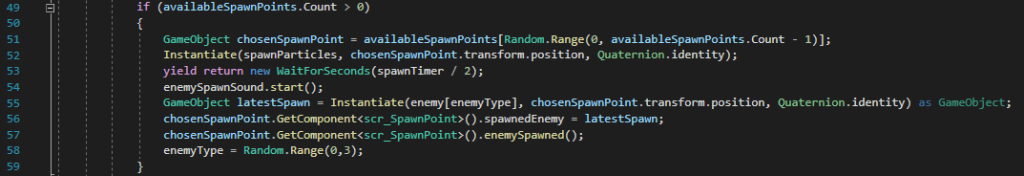

If there is at least 1 available spawn point, a random one from the list will be chosen to spawn the enemy. First, a particle object will be created there, to give the player a warning that an enemy is about to spawn in that position. Then, the other half of the spawnTimer duration will be waited, and the enemy will be spawned. The spawned enemy will be assigned as a GameObject variable to the spawn point it was spawned at.

Each spawn point has this script placed on it. When an enemy is generated at a spawn point, it is assigned to the spawnedEnemy GameObject variable. While that enemy is alive, the spawn point’s canSpawn boolean is set to false, stopping it from spawning any other enemies. Once the enemy dies, it will wait 2 seconds before setting the canSpawn boolean back to true and flipping the spawn points x-coordinate. As all of the maps are symmetrical, this effectively doubles the number of viable locations an enemy can spawn, as they can spawn on either side of the map for each spawn point, as they swap sides every time they spawn an enemy.

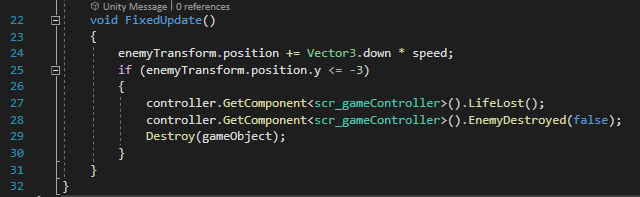

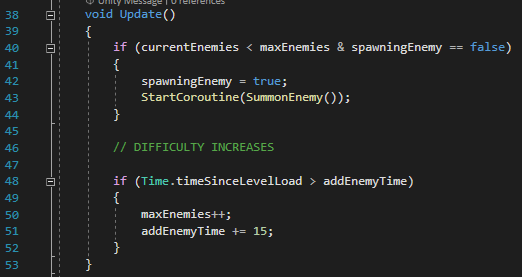

Enemies

There are three types of enemy in the game.

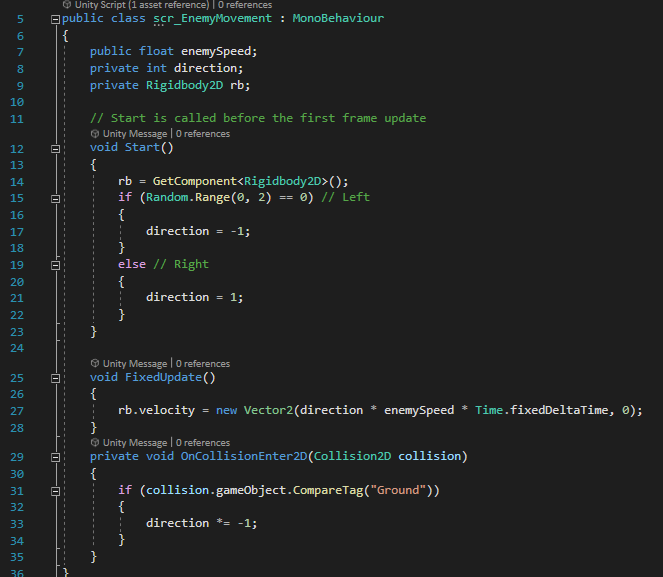

The first simply moves straight in one horizontal direction until it collides with a wall, and then flips to travel in the other way, crossing the screen back and forth until it is defeated. When it is created, it randomly picks a directoin between left and right, and it’s velocity is set in that direction. Upon colliding with a wall, the value of the direction variable is multiplied by -1, swapping it from positive to negative or vice versa, and reversing the direction of movement.

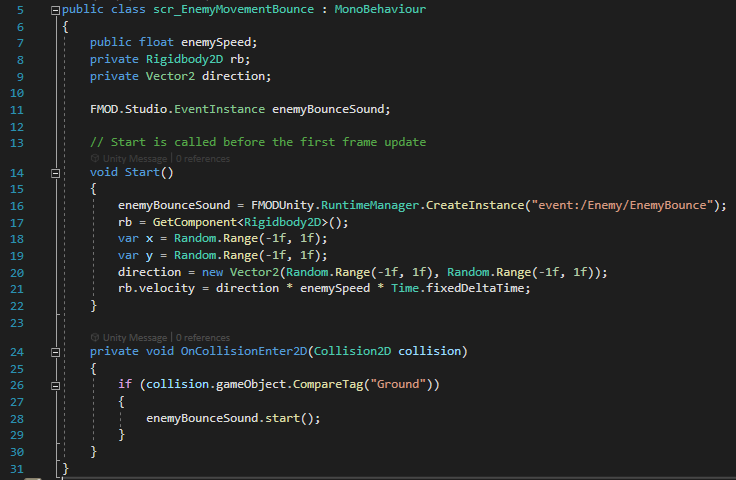

The second enemy type picks a random direction to move in when generated, and moves in a straight line in that direction. The object has a 2D Physics Material assigned to its Rigidbody2D component that has no friction and perfect bouncing, meaning when it collides with a wall, it will bounce off in the opposite direction without losing any momentum. This creates an unpredictable enemy that can catch the player off guard if they don’t pay enough attention to the enemy’s direction.

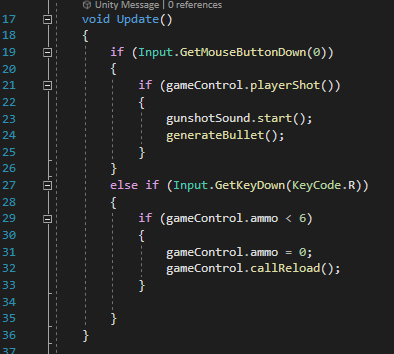

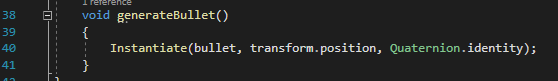

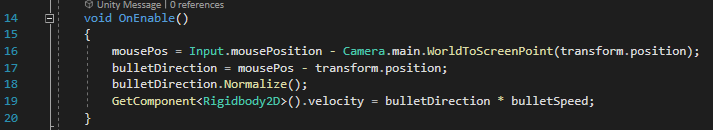

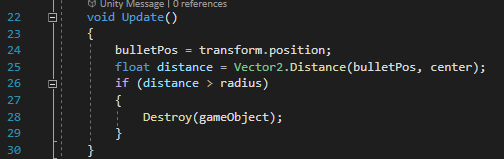

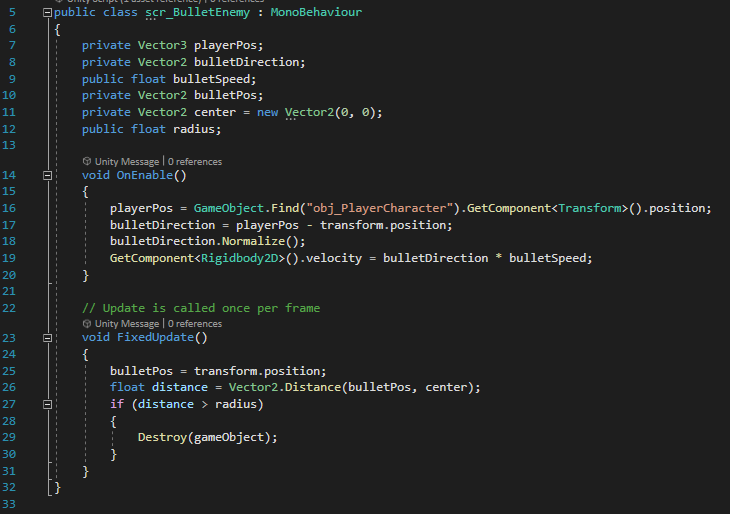

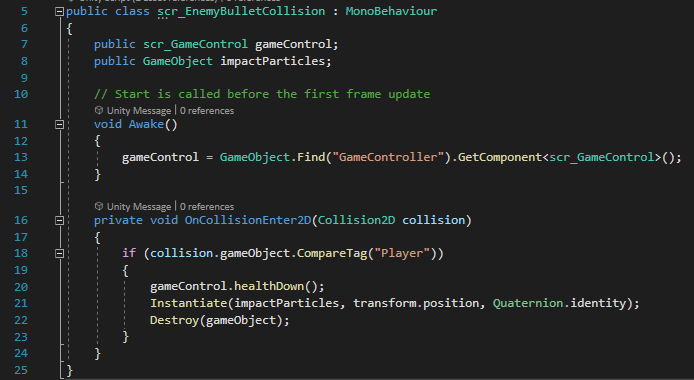

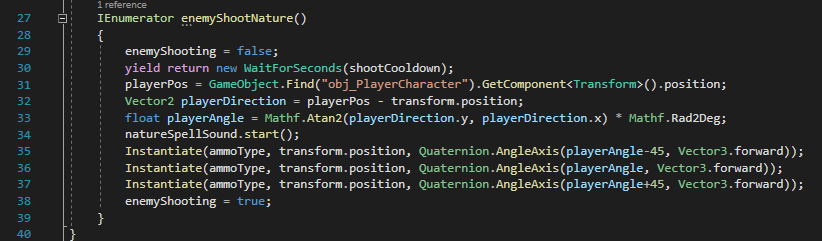

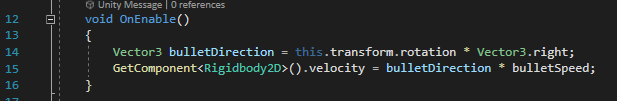

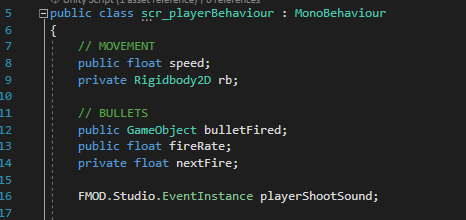

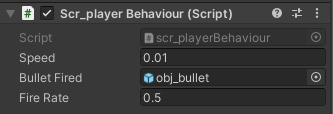

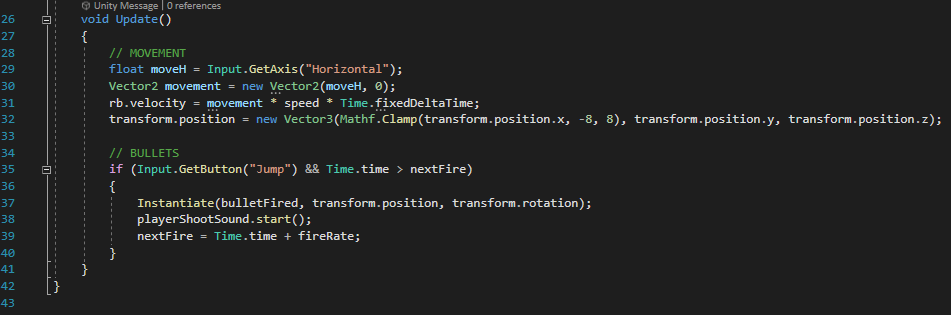

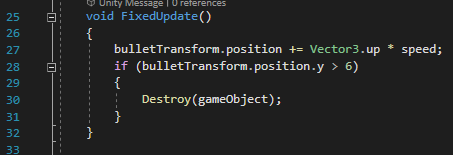

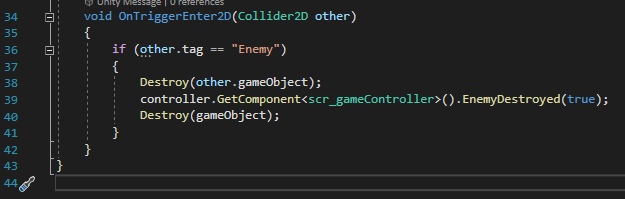

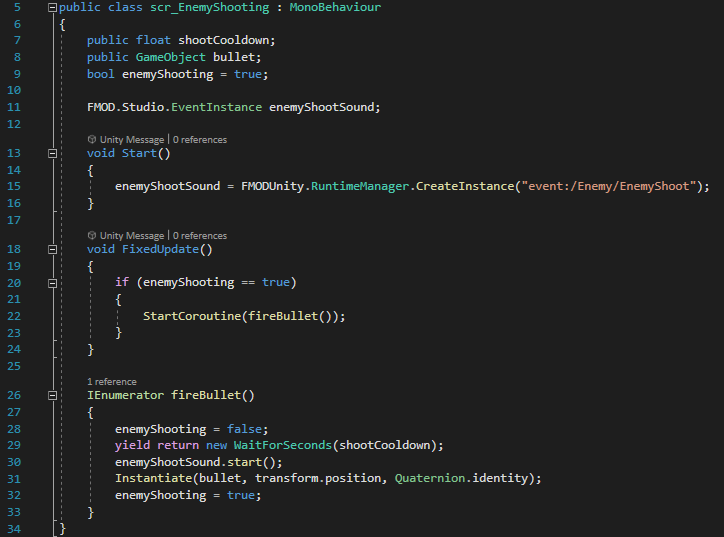

The final enemy type cannot move by itself. Instead, it fires projectiles in the direction of the player, wherever they are on the screen, using a similar script to the projectiles in the Top Down Shooter game – the enemy simply generates a bullet object at its position – the bullet itself, however, has a script that calculates the angle from it to the player’s position at the moment it is instantiated, and sets its velocity directly in that direction, destroying itself if it collides with any other objects along the way.

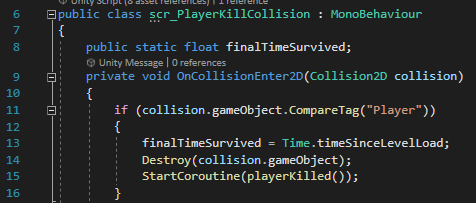

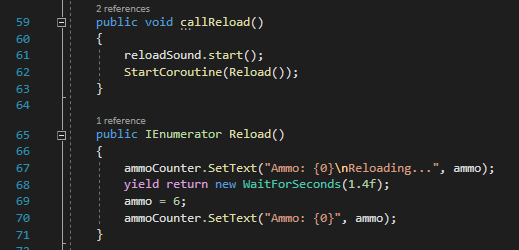

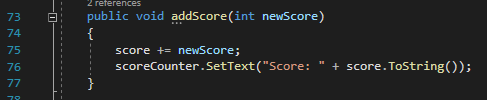

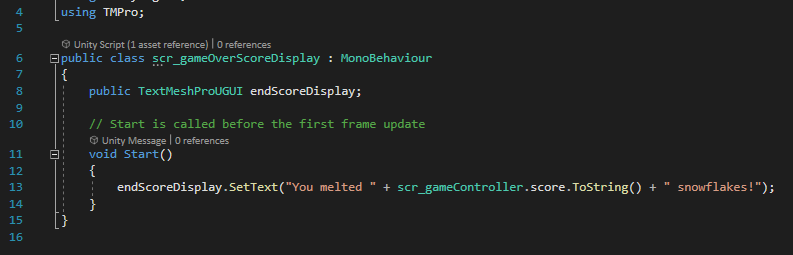

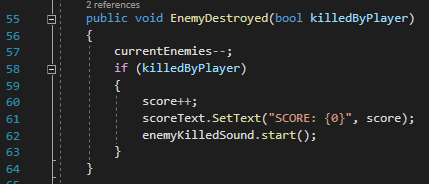

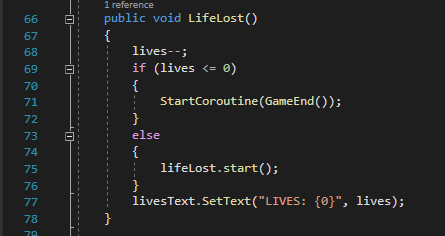

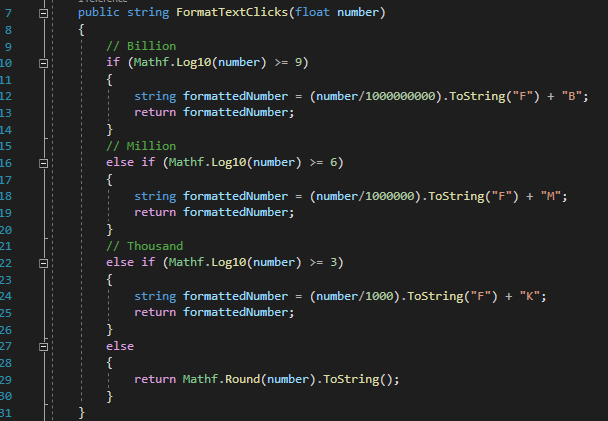

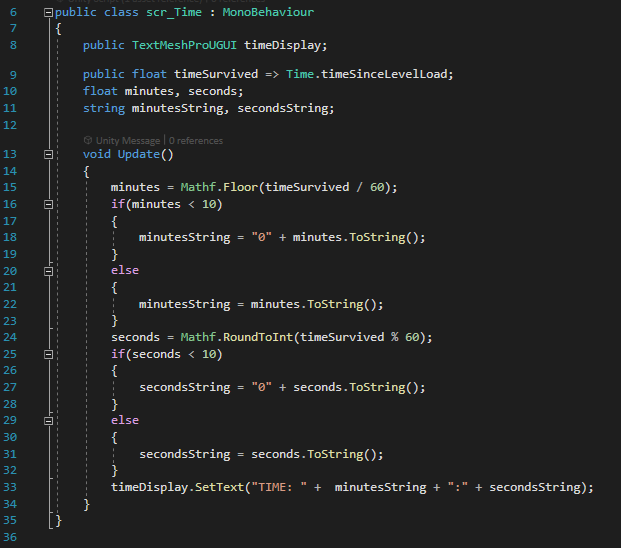

Timer

As well as a score of the number of enemies killed, I added a timer to the game to show how long you have survived. I did this using the Time.timeSinceLastLoad feature built in to Unity, assigning it to a float variable, and then formatting the text to display in a 00:00 format. When the player is killed, the time they survived is stored in a static float variable in the scr_PlayerKillCollision script, and is then loaded on the game over screen to display, along with the number of enemies defeated.